Utopias are, and have always been, about stories of better possible worlds. With the hope that by telling such stories we can shape our experiences, futures, and even memories. In her essay The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction Ursula K. Le Guin critiques the type of stories we often tell. Stories that force energy outwards; that are shaped like a spear or weapon destined to hit an intended mark. Stories that attempt to control or steer the future.

Many utopias across history fit this shape. People conjure up an idea of what a better world might look like, whether through mind, text, image, map or more, and become heroes that strategize and fight to bring it into being. Think of mega infrastructure projects, innovative technologies, and space exploration, but also green energy transitions, protected areas, and tree planting campaigns.

Yet Le Guin suggests there is another way. We can instead tell stories that bring energy home; that are shaped like a sack, bag or bundle. Stories that hold things in powerful relation to each other. These stories do not instrumentalize our imagination in service of predefined ends, but rather create space for difference, and space to differ in how we imagine. They contest those who choose to bleed only their own colors onto the pages of possible futures. Pages that are assumed to be ‘blank’; open to colonize, erase, oppress.

Treating utopia as a carrier bag means not allowing one’s imagination to instantly fill space that is presumed to be ‘blank’. It means not seeking to convince of one’s own beautiful picture, at the expense of the ‘other’. The ‘other’ for whom such utopias may be real (or potential) lived dystopias. But rather bringing people’s imagination in relation with each other; staying with the frictions and struggle instead of quick resolution and harmonies.

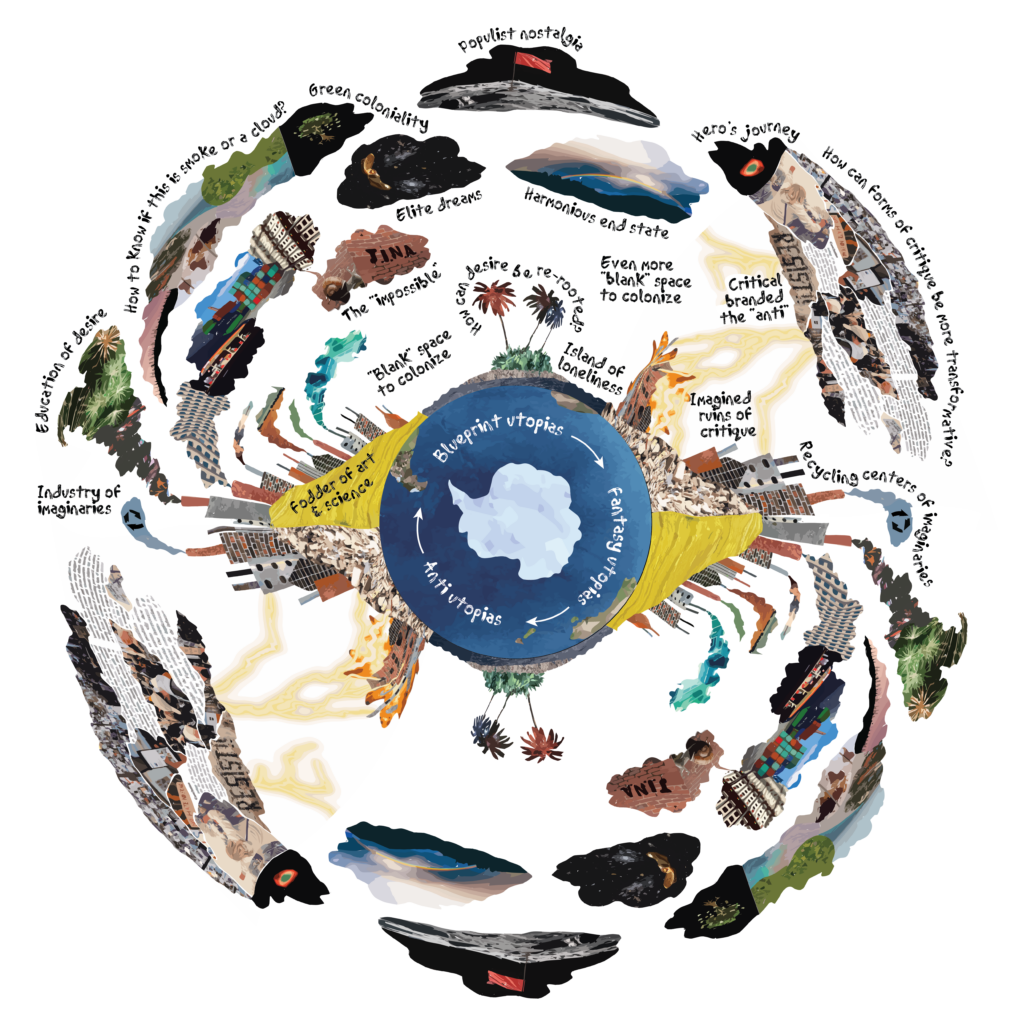

Let’s take this idea seriously and see what happens when we refuse to stabilize a single notion of utopia. When we instead embrace the plurality of ways of seeing the concept of utopia itself, grappling with their oddities, their frictions.

Let’s empty out this carrier bag…

Is this what you expected?

Or are you disappointed?

By missing words?

Or unexplained ones?

What is a heritagutopia anyways?

According to Luca Donner & Francesca Sorcinelli it is the “symbiosis between urban historical heritage and abandoned industrial areas”. Or retrotopia? For Zygmunt Bauman, this is the romantic quest for a status quo of the past. And heterotopias? A more established term from Michel Foucault describing spaces that are ‘other’ in the way they disturb or contradict what is considered ‘normal’ in the broader world.

Or we could also consider the many utopias dotted across history. Thomas More’s Utopia; Edward Bellamy‘s Looking Backward; William Morris’ News from Nowhere; H.G. Well’s A Modern Utopia; W.E.B. Du Bois’ The Comet; Hermann Hesse’s The Glass Bead Game; Ursula Le Guin’s The Dispossessed; José Lezama Lima’s Paradiso; P.M.’s bolo’bolo; Hayao Miyazaki’s Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind; Hakim Bey’s Temporary Autonomous Zone; Toni Morrison’s Paradise; Georgi Gospodinov’s Time Shelter; Pablo P. Castelló’s Zoolondopolis. To name just a few. Or perhaps what comes to mind is something more lived or practical, such as intentional communities, or ‘Real Utopias’, as Erik Olin Wright says. Or the utopias of architecture? Spatial mapping? Or something else entirely?

In this piece I aim to explore some of the critical distinctions that cut across the myriad of terms, expressions, and imaginaries of utopia. Yet this is no in depth account of utopia’s history. There is ironically no space for that here. Although there are many partial attempts to admire: Ruth Levitas’s The Concept of Utopia—a tour of through the meaning of utopia throughout history; Carlijn Kingma’s A History of the Utopian Tradition—a visual journey through 42 Western utopian writings; or Qiu Zhijie’s Map of Utopia—utopia through the historical lens of political ideology. To name a few.

If we return now to imagining utopia in the shape of a carrier bag, what might we find inside? What are some of the key differences that underpin the ways utopia is conceived of, and what how it functions in the world? I will continue with Le Guin’s critical distinction—between utopia as a hunting spear, forcing a binary distinction between ‘the hero’ and ‘the other’—binary utopias; and utopia as an ambiguous carrier bag—full of intricacies, journeys, temporalities, confusions, delusions, failures—ambiguous utopias. Let’s explore some shades of utopia that manifest.

Binary utopias

We say we want a better world. We call for transformative change—no, radical change. We even dream of utopia. But who is this ‘we’? Whose vision is manufactured? What and who has been erased in the making and defending of this ‘we’? This industry of imaginaries is growing, pumping out smoke at an ever-growing speed, fueled by science and art. A ‘science’ and ‘art’ that have been sorted, separated, severed from (e)motion and reduced to fodder. A ‘science’ which defends its use value by offering up so called truths. An ‘art’ which is logically steered by imaginaries rather than free to redefine them.

We see the smoke of this industrial complex creeping forward all over the world, into so many blank spaces—no, imagined ‘blank’ spaces. It glides forward, friction-less, bestowing its pungent odor. Or perhaps that is not a patch of smoke but rather a distant cloud? A sparse cloud sweating in the heat, gleaming silver at a distance yet metallic to the taste as it nears the ground. With soil that has been cut off, banished to the island of loneliness. A place where there is fear, anger, even joy, but little feeling of what people feel. You could say something is broken (and indeed so many have!), yet somehow the cycle continues. It is both the severity of frictions across worlds and their absence within worlds that serve as fuel. And yet we still say we want a better world. We still call for transformative change—no, radical change. We still dream of utopia.

Ambiguous utopias

We say we want a better world. We call for transformative change—no, radical change. We even dream of utopia. But we are many, and many dream of different utopias, worlds apart. Utopias that are inevitably another’s real or imagined dystopia—past, present and future. But how can we stay with these frictions between worlds? How can we not only understand them, but really feel them. Feel where they come from. Feel the solidarity of being willing to understand the other. To change one’s own utopia to include the other. No, that’s not enough. To become utopian together so that many worlds can flourish.

Ursula Le Guin calls such utopias ‘ambiguous’ in their refusal of easy binary commitments to good or bad. Just like Thomas More’s original island of utopia: was he sketching a ‘good place’ to strive for, or ‘no place’ to be dismissed? No one knows. Perfection and clear stances may help stage or avoid frictions. But ambiguity and committing to beginnings rather than only ends, may allow us to navigate the frictions inherent to our diverse dreams. Not just dreams of possible futures, but also imagined pasts. Can we treat utopia in a more ambiguous way? Breaking down the binaries between openness and closure; possibility and impossibility; friction and solidarity; art and science? Could this enable a plurality of alternative utopian politics which, while ambiguous in many ways, remain steadfast in their commitment to resist unjustified closures of collective imagination, and to counter the present?

Prefigurative utopias

We might see glimpses of possible worlds. But what use is it to only peek through a keyhole? Can we enfold these worlds into the present? Make them possible. Play with them. Foster solidarity around them. Grow seeds into moons. Not that linear kind of growth. The branching kind that grows upwards, rootwards, sideways. And moons that glow with grief of what we have lost and hope of what we long for. Like Ernst Bloch’s utopian impulse. And Philip Glass’ song ‘Choosing Life’ in the film The Hours. Art carries the currents of our desires; deepens our glimpsing and making of the otherwise. Artistic research helps us dance on the tightrope between possibility and impossibility, giving courage and skills for when we inevitably fall off. There is so much to learn from: The Zapatistas, ZAD—Zone A Défendre, Quilombismo, Initiative for Indigenous Futures, NSK—Neue Slowenische Kunst, Institute of Radical Imagination, Framer Framed, BAK—basis voor actuele kunst, Alterotopia, and so many more. So many collectives, social movements, prefigurative politics. And still, what are we not prefiguring and why?

Disruptive utopias

Imagination can be seen as friction-less. A speeding car. Or a flight taking off, soaring to greater heights. But this is precisely the kind of imagination that can be so dangerous. An imagination without friction. One which is not forced to grapple with those who would resist it. Those who are actively harmed by it. But why is there so little friction? Power? Extractivism? Ideology? But wait, there is so much friction, with no shortage of polarization, protests, critiques. People who feel robbed of their future, and their pasts. Such imagination can feel like oil in water, struggling to connect and transform. Refusing to be transformed itself. So what new layers of friction can be surfaced, and staged? How can layers of memories, experiences, and dreams, intertwine in novel ways, like Sarathy Korwar’s song ‘Utopia is a Colonial Project’— subverting eurocentric ideals into polyrhythmic dreams. How can we embrace the textures which modernity is so quick to pave over? And create turbulent seas that flip some of our dominant ways of seeing, knowing and being in the world? To stop calling utopia impossible, and start seeing our common sense order as impossible to accept. How can we creatively introduce new kinds of frictions that allow themselves to be transformed?

Speculative utopias

Radically experimental jazz musician Sun Ra once said “imagination is the key that unlocks the door to new worlds”. It may be hard to envision how such ‘new worlds’ connect to our now world, but we also lose something when we quickly reduce our dreams to the possible. Think of ‘Real Utopias’5. To only do what can easily be proven possible also keeps us trapped in our existing realities. In contrast, dreampolitik, the art of the impossible, can estrange us from our ideas of how the world must be, orienting our critical and prefigurative efforts. It can give space for others’ imagination to become activated, to walk deeper into the tunnel of increasingly deeper and more plural speculation until a bridge to the possible can be found—all the while dancing to the tune of Sun Ra’s ‘Door of the Cosmos’. Like the multi-media cartography experiment The World We Became: Map Quest 2350, which presents a planetary vision of interspecies justice intertwining ecological crises with Black, Asian, Pacific, Middle Eastern, Latin American, Caribbean, and Indigenous futures. And there are so many rich speculative worlds to engage with, from Ursula Le Guin’s creations to Nnedi Okorafor’s. And so many more to still build and provoke with. So what is it that makes a speculative utopia transformative of the present?

Pluralizing utopias

With utopia, we often focus on what worlds WE want to make or unmake. But who is this WE? And who is not? And what about the very connective tissue that lies between our worlds, shimmering with radical possibility? Lying between our performative loops of utopia, which continue to reproduce the same tired notions of desirable imagined futures and desirable actions in the now. Loops of self-fulfilling back-casting, yet casting us backward; trapping us with the same master’s tools that “will never dismantle the master’s house”. How can we create space to surface these multi-shaped performative utopias and be willing to step into each others’ worlds? To experience for whom our own utopia may actually be dystopia. And break these cycles, sampling and transforming the old into that which challenges and pluralizes it. Like Ensemble Mik Nawooj’s ‘Bach on Transcendence’. What about the immense power of theatrical, musical, and visual ways of surfacing our conflicting worlds and hosting human connection between them? Like Empatheatre in South Africa, which creates amphitheaters for empathy that foster participatory justice and inform legal battles. How can we experiment even more radically between worlds? And also with those speculative (financial, policy, etc) worlds that are now so dettached from our shared humanity?

Dreamholding

We dream of utopia. We often bring our stakes along as something to hold on to. But we are many and stakes are sharp. Stakes mark boundaries. Stakes keep one trapped. For ambiguous utopias to flourish, let’s focus instead on the vastly different dreams we hold. Dreams are fuzzy. Dreams can permit the impossible. Dreams can challenge boundaries. Dreams can cultivate solidarity. Dreamholding is a continuous and inevitable part of our daily lives. We are always clinging to particular dreams of past, present and future, and repelling others. Dreamholding enables us to more intentionally consider how we cling onto and navigate diverse dreams. It orients us not only towards the present, but deepens the reach of our (multiple) present(s) into erased memories and preposteorus futures. It calls upon artistic research practices capable of surfacing, challenging and transforming our dreams, in ways that give courage to remake our world otherwise.

– Josie Chalmbers

Notes

- Ursula K. Le Guin (1986), The carrier bag theory of fiction, In Women of Vision: Essays by Women Writing Science Fiction, Denise Du Pont (ed), St Martin’s Press

- Luca Donner & Francesca Sorcinelli (2024), Heritagutopia: a new utopian paradigm, City, Territory & Architecture, 11(9)

- Zygmunt Bauman (2017), Retrotopia, Polity

- Michel Foucault (1975), The Order of Things, Routledge

- Erik Olin Wright (2019), Envisioning Real Utopias, Verso

- Ernst Bloch (1986[1959]) , The Principle of Hope, 3 vols, MIT Press

- Stephen Duncombe (2019), Dream or nightmare: reimagining politics in an age of fantasy, OR Books

- Tao Leigh Goffe et al. (2022), The World We Became: Map Quest 2350, A Speculative Atlas Beyond Climate Crisis, Asian Diasporic Vis. Cult. Am., 7(1-2)

- Audre Lorde (1979), The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle The Master’s House, Comments at “The Personal and the Political” Panel at the Second Sex Conference